I’ve been blogging about minimalism for 15 years. Digital minimalism is another form of conscious consumption. And apparently, the topic strikes a chord, because otherwise, Der Spiegel wouldn’t have locked an interview about it behind their paywall (“How to Break Free from Your Smartphone”):

Cal Newport’s Digital Minimalism contrasts with his other bestseller Deep Work in that it doesn’t focus on work and productivity, but rather on our entire lives and the impact technology has on them.

Daniel Levitin’s The Organized Mind showed how easily our brains can be distracted, while Newport presents the opposite side: the attention economy, which primarily benefits those who can successfully market our time to advertisers. Those who think this is a modern phenomenon are mistaken—this started with the introduction of penny newspapers in 1830, where the readers were no longer the customers, but the advertisers in a newspaper.

According to Newport, the unconscious use of social media leads to exhaustion, anxiety, depression, and, above all, a waste of life’s time. Arguments such as social media helping us stay in touch with friends and family are countered by the point that this is not high-quality interaction—more “connection” than “conversation,” as Sherry Turkle distinguishes. When relationships are less digital (or when digital communication is used only to facilitate traditional communication), they are actually strengthened. The time we spend on Facebook and similar platforms is not only spent on lower-quality conversations but also on mindless scrolling through updates that give us the illusion of connection while leaving us feeling lonely.

However, Newport doesn’t advocate for completely abandoning technology. Instead, he encourages us to adopt a different attitude toward it, and he even paraphrases Dieter Rams’ phrase “Less, but better.” This leads to what he calls a digital declutter. Ironically, it was Steve Jobs, who was focused on mindfulness, who ensured that we carry around with us the symbol of constant connectivity in the form of the iPhone. His original goal was simply to have one device for both phone and iPod. The fact that the iPhone could also access the internet wasn’t even mentioned until late in the original keynote. We weren’t prepared for it. And suddenly, there was an app for everything:

We didn’t have time to think about what we truly wanted to get out of these new technologies (and even if we did think about it, like I did back then when I didn’t want a Blackberry, we later found too many reasons why a Blackberry might actually be a good idea). And since then, the door has been wide open for those who want to shape new habits in us:

Nir Eyal’s bestseller Hooked describes this mechanism in great detail. Fairly, Eyal also wrote the antidote to it. However, Eyal’s approach is not as elegant as Newport’s; it deals more with the symptoms, even though it sometimes touches on the causes. Where Eyal says that you can take back your time, Newport suggests you first consider what you want to fill it with. The mechanisms both describe, however, are the same.

Every post for which we might get a like or retweet is, for us, the same as using a slot machine—it triggers a dopamine release. The goal is to regain our autonomy and join the attention resistance, as Newport puts it. Digital minimalism, for him, is:

A philosophy of technology use where you focus your online time on a small number of carefully selected and optimized activities that strongly support what matters to you, while ignoring everything else. (my translation)

To this, he quotes Thoreau in Walden:

The cost of a thing is the amount of what I will call life which is required to be exchanged for it, immediately or in the long run.

This, of course, applies not only to social media & co. When someone buys a new sports car, they also need to consider how much life energy goes into working for that car and whether it’s worth it to drive a sports car in exchange for that time. The profit gained from something must be weighed against the cost of the life energy needed to obtain it. Conversely, technology should be considered optional, as long as its temporary absence doesn’t cause the collapse of one’s (work) life. Can I no longer live a meaningful life without an app, or does the app simply provide some added value that I could get elsewhere? This is in stark contrast to FOMO. To truly understand which technologies are genuinely valuable, Newport suggests a 30-day break.

As I write this, I am on the 8th day of my digital break. Newport really makes this break seem appealing, and I even started it before I had finished reading the book. During the reading, I paused my Facebook profile and deactivated my Twitter account (dangerous, because after 30 days, it is permanently lost). Instagram is deleted, as are Telegram and WhatsApp. These many ways people could contact me had already been annoying. Then, I even uninstalled email. These exact steps were already suggested in Make Time, but for Newport, it’s not about dogmatically banning all these apps, but rather about understanding what you truly miss.

In fact, I only bought my last phone because I wanted the best camera and didn’t want to carry around another camera. I enjoy listening to music. And occasionally, I like to make calls. So, here’s what my home screen looks like now:

Of the slot machines, only Signal, Apple Messages, and Safari as a browser are installed. Everything else is either essential (for example, banking—no longer possible without a phone) or helpful (e.g., the Corona app). Additionally, I’ve now set the Do Not Disturb mode as the default. Only my favorites can still call me, but their messages won’t come through either. However, this isn’t just about distraction.

Solitude (better translated here as seclusion and not as loneliness) requires the ability to be undisturbed and not have to react to everything, or the freedom from input from others. Seclusion demands that we come to terms with ourselves when we are alone, allowing for deep thinking. Our desire for social interaction must therefore be complemented by periods of solitude. How much this already occupied me 14 years ago is shown in this blog post from 2007.

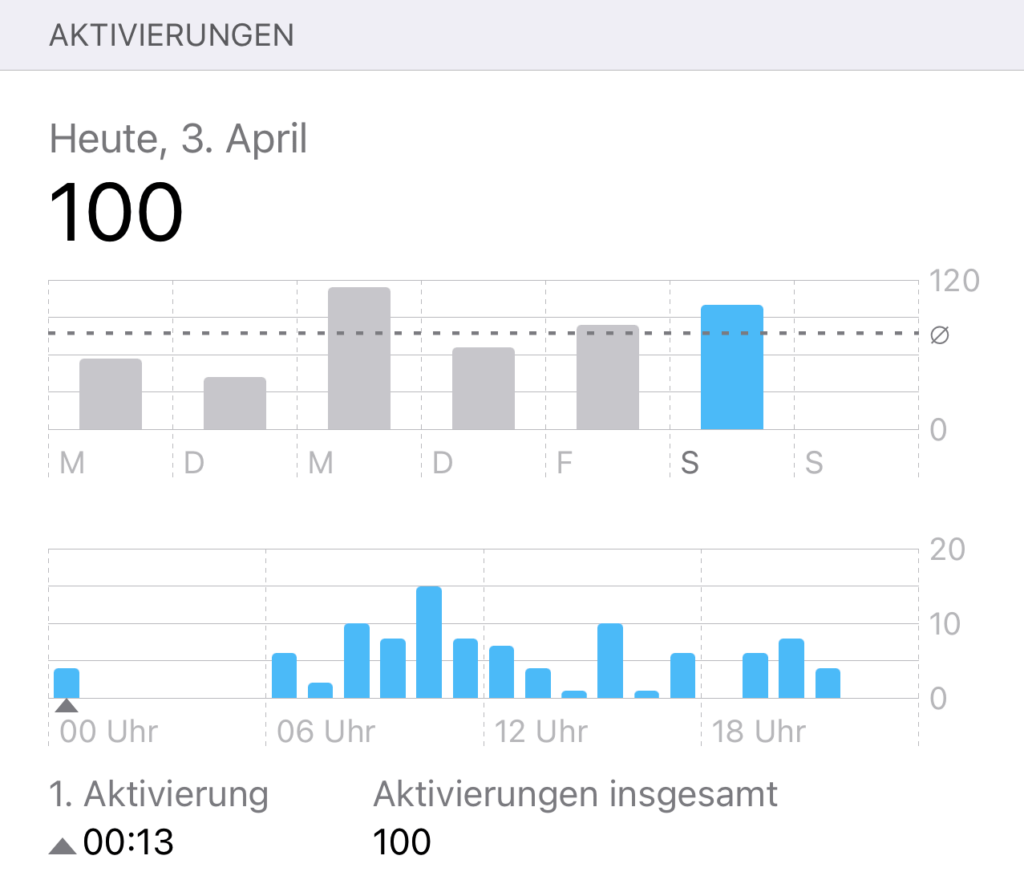

But Newport goes even further. It’s not just about stopping certain activities; as mentioned earlier, you must also consider what to do with the time and attention you’ve gained, so you don’t fall into a void. The smartphone allows us to quickly escape such moments. Most systems already track how often that happens:

(On that day, I made several changes to the configuration, which is why the value was so high.)

Newport suggests writing letters to oneself, engaging in real conversations (instead of chatting, liking, or commenting), joining an offline group, or doing something non-digital with your hands. I’m out when it comes to crafting, but at least I can play instruments. The point is to deliver your best, quoting Rogowiski:

Leave good evidence of yourself. Do good work.

Not using Facebook and the like should therefore not be seen as a sign that you’ve become some kind of eccentric. It should be viewed as a bold act of resistance against the attention economy. This has become increasingly difficult, as we now carry a full-fledged computer with us at all times and actively have to seek ways to limit its possibilities. Still, my reMarkable is one of my favorite work tools. I can’t check emails on it or quickly look something up. And more and more, I’m only using that device when I sit on the couch in the evening.

Furthermore, Newport’s approach means that you need to carefully examine where you still want to gather information. I reactivated Twitter after a week, but unfollowed almost everyone because I only want to follow those who truly provide valuable content. And that’s a very small number. A kind of information diet, so to speak.

I’m not at the point yet where I want to have a Light Phone or leave my smartphone at home most of the time (the Light Phone isn’t available in Germany yet). For now, the camera in my phone is still too important to me (I used to always carry a Fujifilm X100, whose battery was always dead at the critical moments). But after just a few days of digital break, I can already hardly imagine going back to Facebook or spending the first minutes of my day reading through feeds.